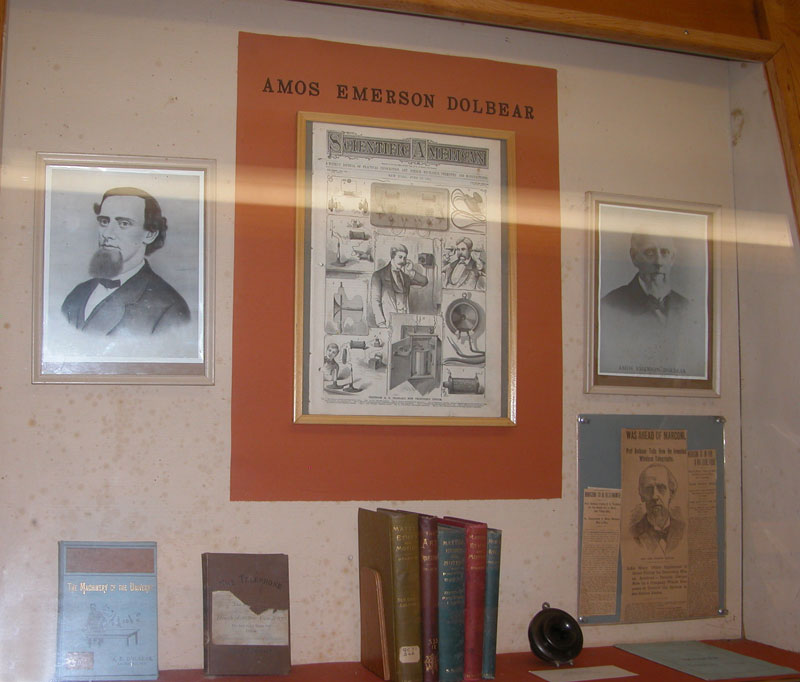

1880 was the same year that Edison perfected the light bulb. Also, the evolution of electrical signaling engineering was ignited about that time, mostly by Edison. But there were other prominent people, like Amos Emerson Dolbear, who was a professor at Tufts College, and neither Edison, nor Dolbear, nor anybody else understood the electromagnetic wave. That waited on Heinrich Hertz’s research, which came a decade or so later. But these guys knew the effects, and they were experimenting with it. And Dolbear had an elevated antenna, and essentially what he was doing was exciting the area around his antenna electrostatically, and the electrostatic field went out. This is not radio waves, it’s just an electrostatic field, and Dolbear was able to signal over a mile away from Tufts College. Dolbear’s patented receiver was nothing but an electrostatic receiver…basically two metal diaphragms very close to each other, so that as the voltage varies on them, the electrostatic attraction moves the diaphragms and makes sound. This is an actual Dolbear 1881 wireless receiver. That has to be one of the earliest wireless devices around. It’s described here in this 1881 Scientific American.

Dolbear, naturally, tangled with Marconi. Marconi had a lot of money because his mother was a very wealthy woman, and he ran to the courts immediately…he was a very action-minded guy. He would sue you at the drop of a hat. Anyway, all of these newspaper clippings are about Dolbear’s difficulty with Marconi.

Anyway, Dolbear was a pioneer, but a forerunner-type pioneer.

Text from the transcript of a tour of New England Wireless & Steam Museum’s Wireless Building given by Robert W. Merriam on a winter day in 2012. Transcription by Craig H. Moody, K1CHM. Edited by Fred Jaggi.